Since we recently experienced the full solar eclipse on August 21, let's take a look back at how this celestial phenomenon affected the great American innovator of the Gilded Age.

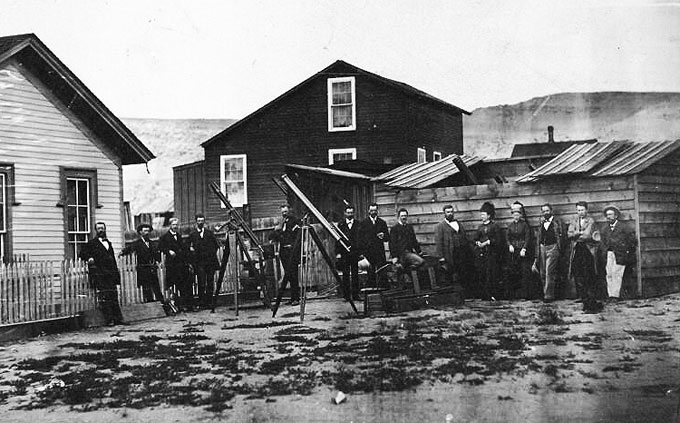

Henry Draper's eclipse party with telescopes in Rawlins, Wyo., in the summer of 1878.

Thomas Edison is second from the right. (Carbon County Museum photo.)

A total solar eclipse can be an utterly surreal experience. As daylight fades, unusual crescent shadows sprinkle the landscape, until the sun is replaced by a black ball suspended in the heavens, a halo of light flickering around. Being within the "path of totality" – in which the sun is completely covered – has been likened to a spiritual experience, one that profoundly affects mere mortal men and women.

Even those destined for immortality themselves, like Thomas Edison.

Edison's introduction to this celestial phenomenon came during the summer of 1878. By that point, at the grand old age of 31, Edison had already accomplished more than most people could dream of in a lifetime. Dubbed the "Wizard of Menlo Park" – the site of his New Jersey laboratory – he was fresh off the invention of the phonograph, which he triumphantly displayed at the Smithsonian and to President Rutherford B. Hayes in Washington, D.C.

Yet, the largely self-taught inventor longed to be taken seriously as a scientist. Emboldened by the reception his phonograph received from America's National Academy of Sciences, he accepted an invitation to join one of the expeditions west for a viewing of the total solar eclipse on July 29.

While largely forgotten until fairly recently, the eclipse of 1878 was a major event for the scientific community and is written about in the new book American Eclipse by author David Baron. With European scholars largely looking down at their counterparts across the Atlantic, this was the chance for Americans to make a mark in academia through contributions to the study of cosmic activity. Among engaged participants, James Craig Watson of the University of Michigan was determined to leverage the conditions to prove the existence of a planet between the sun and Mercury, known as "Vulcan." Meanwhile, Vassar College astronomer Maria Mitchell aimed to head her own expedition to demonstrate that women were more than capable of crashing the patriarchal scientific party.

Edison himself intended to use the event to debut his "tasimeter," a highly sensitive thermometer designed to measure the heat spewed out by the sun's atmosphere, the corona. After arriving in Wyoming territory in late July, he tested his device on the red giant Arcturus, recording minute changes on the bright but distant star.

Unfortunately, the main event proved a different story. While the weather held up for the sky gazers on July 29, winds that lingered from the previous day's thunderstorm threatened to topple the henhouse used to protect Edison's creation. When the full eclipse set in for its three-minute duration, the tasimeter proved way too sensitive for the overpowering emissions of the corona and failed to deliver any accurate readings.

The tasimeter experiment was reflective of the overall endeavor, which led to some breakthroughs but failed to generate a headline-grabbing discovery that would shake the public. The big takeaway was that Watson had supposedly gotten a glimpse of the mysterious Vulcan, and he spent the rest of his short life trying to devise ways to get a better look, though we know now the planet only exists in the fictional world of Star Trek.

Still, progress is often made in less direct ways. After the scientists packed up their gear, Edison continued with colleagues to explore the great West, visiting the peaks of Yosemite and descending to the depths of a Nevada mine, all the while sleeping under the stars. Their imaginations freed, and minds still processing the visuals of the recent eclipse, the friends got to talking about the principles of lighting and transmission of electric power.

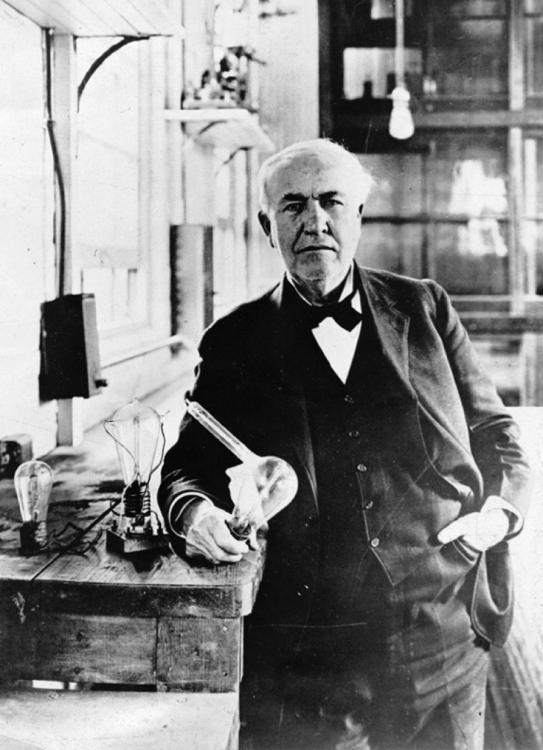

Thomas Edison and his bright idea — the practical incandescent bulb to light up homes which he introduced in 1879.

When Edison returned to Menlo Park in late August, he immediately set to work on the creation that cemented his place in history; the following year, he introduced the practical incandescent bulb to light up homes, physically and metaphorically lifting humans out of the dark.

Maybe there's an epiphany to be gleaned by all of us during the upcoming eclipse. At the very least, it's a good time to step out of work or pull our noses out of our devices, look to the heavens (through safe viewing glasses!) and reflect on who we are amid this impossibly vast universe.