Adam Savage tells the story behind American Epic, the culmination of a two-decade-long project to reassemble a one-of-a-kind 1920s recording system and the exhausting restoration of hundreds of the era’s forgotten musical works.

Here at AMI it’s our duty to report on and analyse all the major technological developments in our industry and predict where we could be heading next, but that doesn’t mean we can’t also look back fondly at the way things used to be.

And we’re not alone, of course, as shown by the success of the American Epic film series recently broadcast on PBS and the BBC that explores the pivotal recording journeys in the US at the height of the ‘Roaring Twenties’, when music scouts from record companies armed with cutting-edge kit ventured out of their studios in the cities in search of new styles and markets.

The three-part American Epic documentary represents the end result of a ten-year project involving – among many others – director Bernard MacMahon, producers Allison McGourty and Duke Erikson; audio engineer Nicholas Bergh (pictured, above); and producer Peter Henderson.

The team was tasked with tracking down legions of long forgotten musicians, restoring their music and recreating one of the revolutionary Western Electric recording systems that would’ve been used to record it, all with help from some of today’s biggest stars.

Breaking it down

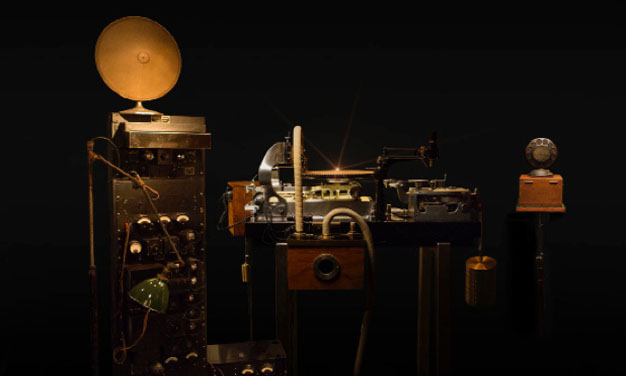

Now the only one of its kind anywhere in the world, the remake of the system that offered the first major step forward from acoustic recording consists of a single microphone – the earliest example of a condenser – a towering six-foot amplifier rack comprising the preamplifier, a line amplifier to drive the cutting head, the first level meter, a monitor amplifier and a live record-cutting Scully lathe – the rarest and most difficult part to find – powered by a weight-driven pulley system of clockwork gears. Musicians have roughly three minutes to record their song direct to disc before the weight hits the floor.

Bergh, who also runs Burbank-based audio restoration company Endpoint Audio, was the man responsible for sourcing and assembling the recording system, but this had been a goal of his since way before American Epic had even been conceived, and turned out to be a much more difficult process than first expected.

“It’s getting on to almost 20 years from when I started but the wacky thing about it is there’s only been about ten years since the equipment’s been starting to come together because for at least the first five years the goal was just figuring out what I was trying to find,” Bergh recalls. “There were no pictures or documentation so I didn’t know what I was exactly looking for.”

The difficulty of Bergh’s quest became yet more apparent when even those who were working in and around the industry shortly after this period had no way of really helping him.

“I had two mentors when I was getting into audio who started their careers in the late 1930s in America and both of them told me that even by the late ‘30s this system was basically mythical and they had never seen any components of it or even pictures,” he says. “So even in ten years it had basically disappeared off the face of the earth. All the pieces that were saved were saved almost by accident, so maybe they just ended up in a spot where no one threw them out.”

Eventually, though, after nearly two decades of scouring the globe, the last piece of Bergh’s puzzle fell into place about a year before the film started to come together, and it was during a public presentation that the makers of American Epic identified Bergh and his (re)creation as a perfect fit for what they had planned, even if there was a bit of work to be done in order to ready the system for what turned out to be a pretty full-on schedule.

“That [the presentation] was just kind of like a laboratory situation where I recorded a musician with the system to demonstrate the frequency response and all the technical issues with the system, but moving that into a production environment, that was a major change,” Bergh reveals. “It had to be updated with easier cabling, for example, and they were bringing in a couple of musicians a day. The gear had to be working at all times so I was fixing little things that were going wrong.”

Meanwhile…

The musical restoration side was overseen by Erikson, sound engineer Joel Tefteller and Henderson, whose past achievements include winning his first Grammy at age 23 for producing Supertramp’s Breakfast in America.

Henderson’s role required him to spruce up around 200 recordings of varying quality, and, like Bergh, a lot of his time was spent hunting for material.

“The first part of the chain is to find the very best copy you can, calling all the collectors to find out what they’d got and whether they had certain discs and what condition they were in,” Henderson told AMI. “Once we’d located what we’d thought were the best discs of each one, they had to be transferred into the digital domain. We learnt a lot during the process.

“Every single disc was different and some labels had used a better shellac that had lasted longer, for example. In some cases we were lucky enough to get some metal parts – that’s the originals where they were cut to wax and the metal was put into the grooves and the discs were printed from those back in the ‘20s. Some of those still exist – Sony had some of them in their vaults – [but it only amounted to] 15-20 discs out of the whole 200.”

If Henderson had to identify a batch of the recordings that gave him the most trouble, what would he pick?

“Some of the Charley Patton recordings were very noisy just because they’re Paramount Records and they’re the hardest to restore,” he says. “There’d be so much noise, and that’s very difficult to remove manually.

“It’s a great project because there are a lot of people who don’t know this music from this period of time. Electrical recording started in 1926 and it really was the first time that you could record music in a way that it was nice to listen to. It’s all part of the history of music that continued on from that point. Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton – all their music reverts back to this lineage, and the same with the folk music from that time. That lineage is all a little bit forgotten.”

And yet there’s more

American Epic Sessions, a feature-length film made alongside the series, saw Jack White (pictured below) and T Bone Burnett – executive producers for the main doc – invited to produce an album of recordings from 20 well-known artists, including Alabama Shakes, Beck, Elton John and Willie Nelson.

The list of participating musicians varied greatly not just in genre but in familiarity with different methods of recording, meaning some took to it quicker than others, but having White – also owner of Third Man Records and his own vinyl pressing plant, as well as a general old-style recording enthusiast – on board was a clear benefit.

“I think in general they all really dug it but it was really great to have Jack there to help with the musician side because he really got to understand the system quickly and was really helpful with the arrangements and moving musicians around and things like that,” states Bergh. “It’s a very tricky microphone to use so it’s very different for people who are used to using a Neumann.”

And because recording direct to disc would’ve been a new experience for many of these stars, there must have been a lot of takes? Again, it depended on the artist.

“Some of them were used to being acoustically balanced and doing things in a live way like that, like Willie Nelson for example, and they just kind of sat down and knocked it out, or maybe they did one take and we’d readjust the mic position a little bit and then once they’d done the second take that was it,” Bergh says. “Other artists are more used to doing produced recordings in the studio and maybe there would be a dozen takes before we could dial everything in.”

Henderson adds: “What Nick was doing with that machine was making it possible for contemporary artists to see how difficult it was to capture something in one take. A lot of people have done direct to disc using very hi-fi equipment, but it’s still an enormous challenge and most artists couldn’t do it because it’s too hard and you always want to tweak and change things.”

All of the audio heard from the performances shown in the feature are taken straight from the discs they were recorded to, with no editing or enhancements made, and you’ll have to check out the film yourself to develop your own opinion on how well the recordings came out, but when asked about the quality of recordings from this period in general compared to what we’re subjected to in 2017, Bergh offered a mixed response.

“From a technical side everything is wrong with the shellac recordings from this era – the frequency response is poor, the noise is high, but they have qualities that are harder to quantify and have advantages over what we can do today and that’s due to the simplicity of the system and the lack of mechanical damping,” he explains. “The microphone and the cutting head are significantly less damp than anything used today, and so the transient response is quite impressive and recordings tend to be more lively and wild sounding in a way than anything we’re used to today.”

Taking time to adjust

For Henderson and Erikson, it took quite a while to adapt to the characteristics of these old recordings, and even though some of them needed a real effort to make them useable, they could only go so far in order to maintain legitimacy.

“It’s just one microphone recorded direct to shellac, which offers a very different sound and you just have to get used to that. It took our team about three years to get our ears established – a little easier for Duke and myself because I’d started off at AIR Studios working with George Martin back in the ‘70s and Duke had been in a band [Garbage] and produced so our ears are a little bit more attuned to listening but it takes a lot of time to understand.

“What you really don’t want to do with this material is try and clean it up to make it sound contemporary as that just doesn’t do justice to the original recordings, which are amazing. All we’re trying to do is the minimum amount of restoration and do nothing that damages the integrity of the sound – that was our premise for the whole thing.

“We ended up doing a lot of manual restoration, which is so time consuming and mind numbing – hours and hours taking out clicks manually rather than using algorithms that can’t really differentiate between the music and the clicks.”

So how does Bergh feel now that not only has he completed his two-decade-long quest, but he’s also owner of the only Western Electric recording system of its kind in the world and if it wasn’t for him then this much celebrates project wouldn’t have been possible? And now that this has all finished, what’s next for him?

“It feel great, but the weirdest thing for me is just watching the film because I’ve spent so many years looking at these terrible grainy photographs trying to figure out what these things were,” he explains. “My initial goal was to go to the library and read someone else’s research on this – it was never really my aim to do this – so I just hope that other people will be able to have it easier, see and understand it and learn about it. For the recording industry especially there’s very little before the war about what was happening at the major studios.

“I’d love to explore other areas a little more, so I’d like to do more with acoustic recording and the next era after this one, like the mid-1930s, which I’m very interested in as well, but I’m just plugging away filling the holes in the historical record of sound recording.”

Courtesy of AMI