A century ago, a recording of the startlingly novel “Livery Stable Blues” helped launch a new genre of music unknown to most of the rest of the United States.

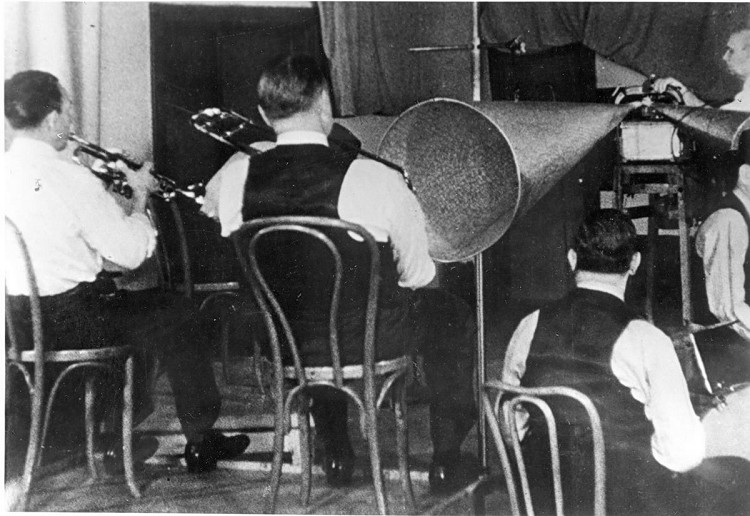

One hundred years ago this month, five New Orleans musicians in the Original Dixieland Jass Band made the first-ever jazz recording in the Victor Talking Machine Co. studio in New York. In this photo, you see cornetist Nick LaRocca and trombonist Eddie Edwards playing into funnel-like metal horns that concentrated sound waves and sent vibrations to a stylus that cut into a soft wax master disc.

One hundred years ago this month, five New Orleans musicians in the Original Dixieland Jass Band made the first-ever jazz recording in the Victor Talking Machine Co. studio in New York. In this photo, you see cornetist Nick LaRocca and trombonist Eddie Edwards playing into funnel-like metal horns that concentrated sound waves and sent vibrations to a stylus that cut into a soft wax master disc.

“Livery Stable Blues,” the first studio number scratched into wax by the Original Dixieland Jass Band in 1917, sold more than a million copies and became the first product labeled “jass.”

Just as events were unfolding in the White House that would solidify public support for entering the war in Europe, a group of five white musicians gathered in the New York City recording studios of the Victor Talking Machine Company and raucously made history.

The day was February 26, 1917. While President Woodrow Wilson was facing the threat of a German alliance with Mexico, the musicians laid down a high-energy, vaudevillian performance of "Livery Stable Blues," backed by the "Dixie Jass One-Step" on the flip side of the 78 rpm disc.

This recording, long argued and debated, is likely the first jazz recording ever issued.

The ensemble—a dance outfit organized in Chicago the year before—was called the Original Dixieland Jass Band (ODJB), which later changed the word jass to jazz. (In that period, the word was spelled variously jas, jass, jasz, jaz, and jazz.)

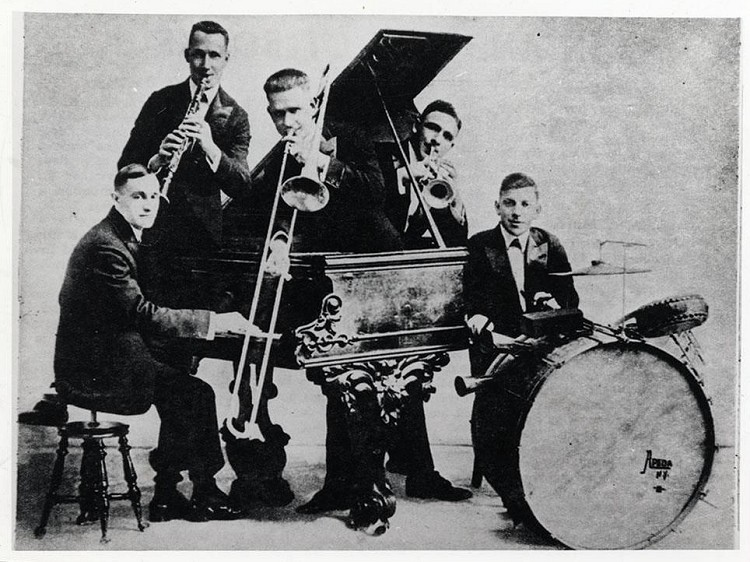

The Original Dixieland Jass Band included cornetist Nick LaRocca, trombonist Eddie Edwards, clarinetist Larry Shields, pianist Henry Ragas, and drummer Tony Sbarbaro. Photo: Duncan Schiedt Collection, Archives Center, NMAH

The Original Dixieland Jass Band included cornetist Nick LaRocca, trombonist Eddie Edwards, clarinetist Larry Shields, pianist Henry Ragas, and drummer Tony Sbarbaro. Photo: Duncan Schiedt Collection, Archives Center, NMAH

The band was led by the Sicilian-American cornetist Nick LaRocca, and included trombonist Eddie Edwards, clarinetist Larry Shields, pianist Henry Ragas, and drummer Tony Sbarbaro. The ODJB had just taken up residence at Reisenweber’s Café, a swanky eatery on 8th Avenue, near Columbus Circle—coincidentally, now the home of Jazz at Lincoln Center. So sensational was the group at drawing large, curious crowds that their gig had just been (or was about to be) extended to 18 months.

The band, with its publicity-grabbing antics and with the word jazz in its name, has taken on a special, if complicated, place in American music history.

More than any other music, jazz expressed the spirit, pride and pain of the black experience in America and its syncopated, swinging sound stands as an ultimate expression of African-American culture. Yet the first band to make a jazz record was white. And in later years, leader LaRocca would incense many by making racist remarks and preposterously claiming that he invented jazz.

The early-20th century was a period of entrenched white racism, but in New Orleans, where there was little racial segregation, blacks and whites lived cheek-by-jowl, everyone’s windows were open and sounds floated from house to house, which meant music was easily shared. In this light, it is not entirely surprising that the first jazz recording was made by white musicians.

Record companies routinely ignored African-American musicians—with only a few exceptions, such as singer Bert Williams and bandleader James Reese Europe. It wasn’t until the 1920s that record labels discovered a growing market, largely among African-Americans, for black music.

Some scholars would prefer the honor of the first jazz recording to go to the African-American instrumental quartet the Versatile Four, which on February 3, 1916, recorded Wilbur Sweatman’s "Down Home Rag" with swinging rhythms, a strong backbeat and a drive that implies improvisation. Or to Sweatman himself, who in December 1916 recorded his "Down Home Rag," playing a solo with an improvisatory feel but a non-jazz accompaniment. Some experts simply say that it’s futile to acknowledge any actual first jazz recording, but rather point to a transition from ragtime to jazz in the years leading up to 1917. As critic Kevin Whitehead put it: “We might do better to think not of one first jazz record but of a few records and piano rolls that track how jazz broke free of its ancestors."

In New Orleans and a few other urban places, jazz was already in the air by the 1910s, and in late 1915 the record companies were starting to discover it. That’s when, according to legend, Freddie Keppard, a leading African-American cornetist from New Orleans, was playing in New York City and received an offer from the Victor Talking Machine Company to make a record.

ODJB makes a record - Livery Stable Blues

For a newsreel, shot in late 1936 or early 1937, the band recreated their first recording session from February 26, 1917. (0:50)

Video Courtesy of Smithsonian Institute

Keppard turned Victor down, the story goes, either because he didn’t want others to “steal his stuff” or because he refused to perform an audition for Victor without compensation, thus losing the honor and distinction of leading the first jazz band to make a recording.

And so it fell to the Original Dixieland Jass Band. Although its recordings reveal a band short on improvisational ability, it never lacked for drive and energy and the American public found the group strikingly novel. The recording of Livery Stable Blues, by some estimates, sold more than one million copies.

“These songs by the ODJB were terrific, expressive tunes that changed popular music overnight,” jazz historian Dan Morgenstern told Marc Myers in 2012. “The impact of their syncopated approach can only be compared to records by Elvis Presley in the mid-1950s.”

ODJB was also the first recorded band to use the word “jazz” (or “jass”) in its name; the tune takes the form of an African-American blues, a major root of jazz; and a number of its early recordings became jazz standards: "Tiger Rag," "Dixie Jass Band One-Step" (later called "Original Dixieland One-Step"), "At the Jazz Band Ball," "Fidgety Feet," and "Clarinet Marmalade."

The band played a lively, syncopated dance music rooted in New Orleans (as well as in vaudeville traditions), and their front line of cornet, clarinet and trombone wove contrapuntal melodies—a sound that still stands as a primary hallmark of New Orleans jazz.

Today’s listeners may have great difficulty listening to this recording. Made before the days of electrical microphones, the recording offers poor fidelity by today’s standards. Moreover, the music is repetitive and doesn’t seem to build to a climax. The group didn’t so much improvise solos, as is the practice today, but rather employed variation and well-rehearsed breaks.

Yet, "Livery Stable Blues" became a smashing success in part because its four breaks convey barnyard effects (hence the alternate title "Barnyard Blues"). At 1:19, 1:37, 2:30 and 2:48, you can hear, in quick succession, the clarinet crowing like a rooster, the cornet whinnying like a horse, and the trombone braying like a donkey.

Rare production footage discovered by film archivists Mark Cantor and Bob DeFlores shows the entire performance of “Livery Stable Blues,” with breaks for the animal sounds at 1:12 and 1:26. Pianist Henry Ragas has been replaced by J. Russel Robinson.

Video Courtesy of Smithsonian Institute

The original phonograph recording from 1917 can be found on YouTube. After disbanding in the mid-1920s, the ODJB reconnected in 1936. For a newsreel, shot in late 1936 or early 1937, the band recreated their first recording session from February 26, 1917. Rare production footage discovered and saved from decay by film archivists Mark Cantor and Bob DeFlores shows the band playing the entire “Livery Stable Blues,” with breaks for the animal sounds at 1:12 and 1:26 (above videos). Pianist Henry Ragas has been replaced by J. Russel Robinson.

Besides the novel animal effects, the music was unprecedented in its lively tempo, noisy humor, brash energy and overall impertinence. Its musical subversiveness challenged established conventions. The band reveled in outlandish stage antics—such as playing the trombone with the foot. And it employed a fun and audacious slogan: “Untuneful Harmonists Playing Peppery Melodies.” Leader Nick LaRocca piqued the press with statements like “Jazz is the assassination of the melody, it's the slaying of syncopation.”

Like punk rockers 70 years later, its group members gleefully proclaimed their outsider status in the musical world.

The band’s social-cultural importance surpassed its music: signaling a break from ragtime, it introduced the word jazz to many people; popularized the music to widespread audiences; by performing in England in 1919, helped jazz go international; and deeply influenced a generation of young musicians, from Louis Armstrong (who liked its recordings) to young white Midwesterners such as cornetist Bix Beiderbecke and clarinetist Benny Goodman. Armstrong would go on to revolutionize jazz and change American music forever; all three became renowned masters of the jazz idiom.

But New Orleans wasn’t the only source of jazz in the 1910s, and New Orleans style wasn’t the only flavor.

During the middle and late teens, in New Orleans, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, New York, Washington, D.C. and elsewhere, black musicians—and their white counterparts—were experimenting. They were trying out looser rhythms, fooling around with given melodies, syncopating and embellishing them, bending notes, devising their own breaks, otherwise elasticizing the original pieces and creating their own tunes.

By the close of the 1910s, jazz had emerged outside the confines of New Orleans, lighting up nightspots in New York and other cities. While expanding geographically, jazz had also moved from the tenderloins into dance halls and vaudeville houses. Through sheet music, piano rolls and especially phonograph recordings, jazz had entered the parlors and living rooms of average Americans, undergoing a transformation from a localized style of music making to a budding and controversial national phenomenon.

What did the advent of jazz recording lead to? Eventually to staggering numbers: since 1917, 230,000 recording sessions have produced nearly 1.5 million jazz recordings.

For the first time, sound recording became essential to a radically new musical genre. What were the consequences unleashed by the success of the earliest jazz recordings? Sound recording transformed the evanescent into the permanent, capturing fleeting improvisations and aural qualities of jazz that cannot be notated. The evolving technology transformed the local into the national and international, enabling this music to go global. Phonograph records vastly increased the music’s listenership; previously, at most a few hundred people could take in the sounds in a live performance.

But recording also divorced jazz from its performance, spatial, social and cultural specifics, limiting it to sound only. Thus, a genteel record-buyer in London could sit back in his parlor and listen to core characteristics of jazz—improvisation, syncopated melodies, “blue notes,” swing rhythms, call-and-response patterns, etc.—without a clue what it was like to hear the music in its original setting—a barrelhouse, café, speakeasy or dance hall. Not see dancers moving to the live music. Not grasp the fluidity of physical and psychic boundaries between African American audiences and musicians, the responsorial exhortations—“Mm-huh,” “Play it!,” “Oh, yeah!”—that black audiences would routinely give performers. Not be able to see how the ODJB musicians exchanged cues and glances, how the trumpeter manipulated his mutes, how the drummer made those different percussive sounds, just how the pianist formed his chords on the keyboard.

Besides conquering space and time, the recording of jazz a century ago created new sources of income for performers, composers, arrangers and the music industry. It set in motion fandom. It led directly to the invention of discography—the systematic ordering of information about recordings. It facilitated formal jazz education in colleges and universities. It helped generate a codified standard repertoire and a jazz canon. It sparked periodic revivals of earlier styles; and it enabled a sense of its own, recording-based history.

That's quite a legacy.

This article originally appeared on Smithsonian.com