A few years after the founding of the earliest record player companies like Pathé by the Pathé Brothers in France in 1896, the Gramophone and Typewriter Company by William Owen in the UK in 1900, and the Victor Talking Machine Company by Eldridge R. Johnson in the US in 1901, Shanghai became the target for this new entertainment.

Editor's note

From a fishing village with a population of just 200,000 in 1843, Shanghai has developed into a huge modern city where more than 23 million people live. From the time Shanghai was forced to open up as a port in 1843, the city has witnessed remarkable change and progress. This year marks the 171st anniversary of Shanghai's opening-up and in this special series of reports, the Global Times will highlight some of the crucial moments, recall some choice memories of olden days and uncover some of the secrets of the city. Don't miss these exciting insights into the metropolis.

Records made by Pathé Orient Photo: CFP

In 1903, the Gramophone and Typewriter Company started recording discs in China. The recordings were all Chinese opera - 329 Putonghua records were made in Shanghai and 147 Cantonese versions were recorded in Hong Kong.

These discs were issued in 7 inch and 10 inch sizes, with the Gramophone Concert Record label and disc titles at their center and the Recording Angel trademark on the other side. They were sold through the British company Moutrie in Shanghai, and on January 1904 Moutrie ran an advertisement (believed to be the earliest advertisement for recordings in China) in the Shen Bao newspaper.

The Victor Talking Machine Company soon followed by offering recordings, also of Chinese opera, in Shanghai in the first half of 1905. These were reissued from 1907 to 1909 with different Chinese brand names. Moutrie later became the first and exclusive sales agent for Victor records throughout China.

In 1908, E. Labansat, a young Frenchman launched the Shanghai-based record company Pathé Orient in 99 Sichuan Road as a subsidiary of the multinational Pathé. He made the seed money for this during the early 1900s with an unconventional marketing ploy. When listeners gathered around his stall on what is now Xizang Road South he would ask them to pay 10 cents while he played a novelty recording entitled Laughing Foreigners (yangren daxiao). Anyone who didn't laugh or smile as they listened to the chuckles, chortles, and guffaws on the recording would get their money back.

A massive program

With a Chinese assistant named Zhang Changfu and a French recording engineer, Labansat started a massive recording program of Peking Opera excerpts. The first series of recordings, which the company went to Beijing to complete in 1909, involved several high-profile artists who had performed for the imperial families in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) or with the most famous operatic companies.

In 1913, the company made a second, larger and more varied series of recordings. A report on the development of Chinese recordings in 1911 in Antique Phonograph News noted that Pathé Orient's recordings almost covered all of the early, well-known Peking and Cantonese opera performers. As well artists from Shanghai, Tianjin, Wuhan, and the provinces of Shaanxi and Jiangsu, among others, had contributed thousands of tracks. These recordings proved to be a hit in Shanghai and Pathé Orient became an important brand, reported Ge Tao, a historian from the Institute of History with the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences.

As well as the impressive number and variety, Pathé Orient distinguished itself from its local competitors by accentuating the authenticity of its product. At that time Moutrie often hired lesser known Chinese opera singers to record so-called Victor discs and then marketed them as the stars. Pathé Orient recorded the excerpts that were the signature numbers of the stars and their most frequently performed pieces so listeners could tell if they were getting the real thing. The company sold each recording with a photograph and a signed authentication from the artist involved.

A gramophone Photo: CFP

The French connection

After recording these first two series of operatic excerpts, the master discs had to be sent back to Paris where the actual records were then made, packaged and sent back to China for retailing. This dependence on the French parent company was eliminated when Labansat established China's first recording studio and record-pressing plant in the then French Concession, at 1434 Xujiahui Road, now 874 Zhaojiabang Road, according to Andrew F. Jones in his book Yellow Music: Media Culture and Colonial Modernity in the Chinese Jazz Age. The plant began operating in 1917.

After that it became the norm to have new records available constantly. In 1922 a new genre entered the scene when the company released four records of Buddhist mantras recited by monks.

In the same year, the company launched three discs of Western music which Shen Bao reported as including the national anthem of France, French and Russian military music, and "famous cheerful melodies from the UK."

Yet throughout the 1920s Chinese opera recordings dominated the marketplace and Pathé Orient was quick to invite new stars to join their library. The historian Ge Tao noted that the all-time best sellers of the period remained recordings of Peking and Cantonese opera with Western music coming in third place. The best seller was a recording by the distinguished Peking Opera star Tan Xinpei in 1909, which topped the Pathé Orient sales charts until in 1921 when the company released a recording by the great female Peking Opera performer Lu Lanchun who lived in Shanghai.

In 1930, the parent company and Pathé Orient were bought out by the British Columbia Graphophone Company but Columbia retained the popular Pathé name and trademark .

A radio of the era Photo: CFP

Production spreads

The British-backed Pathé Orient moved its office from 99 Sichuan Road to 19 Yuanmingyuan Road where it rented 10 rooms on the building's fourth floor and employed 50 or so Chinese and foreigners.

The production plant in the French Concession, on the other hand, was named the China Record Company. This plant not only continued to manufacture Pathé Orient records, but also worked on orders from the local subsidiaries of other European record companies. About 1,500 were employed here.

Although Pathé Orient was making a profit (largely because of the China Record Company), in the early 1930s the company encountered two big problems. The first was that radio had become more widespread and as it developed the demand for recordings fell away. The second involved the Japanese attack on Shanghai in 1932 (the January 28 Incident, or the Shanghai War of 1932), which seriously affected industrial and commercial sectors including Pathé Orient.

The company responded to the new market challenges by introducing electrical recording techniques which produced a better, more resonant sound and it cut the number of Chinese opera recordings made and offered more popular songs.

Most of the Chinese popular songs then were first sung in movies and more often than not by the stars themselves. Getting these actresses to record their songs was a logical move. And, despite their fame, these stars were less expensive to record than the opera stars. The great film stars like Li Minghui, Hu Die, and Xu Yanyan, earned no more than 500 yuan ($82) for making a single recording, a fraction of the amount an opera star could collect.

The new marketing strategy was a huge success and recordings of popular songs - usually released in batches of 10,000-20,000, became the company's primary products and profit source. To maintain and enhance the business, the company went to great lengths to create bands, employ first-rank composers and lyricists and discover new talents.

After the Japanese invaded Shanghai in August 1937, the company's record sales experienced a slight decline but soon recovered. In early 1939 the city experienced a wave of hedonistic escapism and indulgence which encouraged the company to produce new recordings which sold well. The greatest star of the day, the legendary "golden-voiced" Zhou Xuan, recorded 25 of her 31 songs for Pathé Orient.

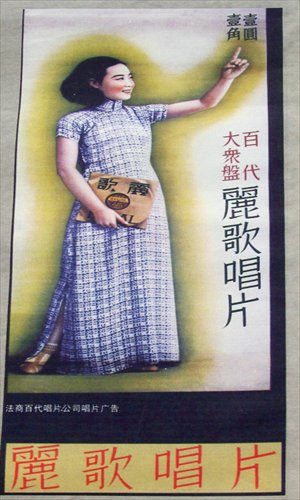

This Regal Records poster featured a happy model with a record.

Regal Records was a branch of Pathé Orient. Photo: CFP

A Japanese star

The Japanese came to power in Shanghai in December 1941 and a Japanese recording company took over Pathé Orient. Like its predecessor, the Japanese company did not change the brand name or the trademark. Between 1941 and 1945, its brightest star was Yamaguchi Yoshiko and her songs were not only widely popular in Japanese occupied areas, the pseudo-Manchu State, and Japan itself, but well-received in areas under nationalist control.

After the Japanese succumbed in 1945 the company was returned to the British and from 1946 several new recordings were made and proved popular - like the 21 songs by Zhou Xuan from 1946. However from 1948 the company saw a sharp decline in sales and in April 1949 it announced it was closing down.

There were also home-grown participants in the record market. In 1917, the Great China Records company, as named by Sun Yat-sen, was launched by Chinese and Japanese businessmen. Then in 1927, 12 Chinese businessmen purchased the Japanese shares, and an exclusively Chinese company officially came into being in April 1929. Another major city record company was Great Wall Records which started in 1930. They were two of the 30 foreign and domestic record companies which flourished at the peak of the Shanghai record industry. By 1949 only 10 were extant and the numbers kept dropping away.

On May 29, 1949, the municipal government under the Communist Party of China took over Great China Records and began recording on June 3. Three days later the first recordings were released. In 1950, the company moved its headquarters to Beijing and renamed itself People's Records. One outlet remained in Shanghai and it was then the one and only recording company in the city.

In 1951, the industry administration and two businessmen launched a new company, the China Industry Department Shanghai Record Company which later became known as Shanghai Records and it used Pathé Orient's plant (on 874 Zhaojiabang Road) as its headquarters.

The record business shrank hugely during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) when most of the recordings produced were confined to songs written from Mao Zedong's quotes or poetry, some modern Peking Opera and revolutionary songs.

A new bloom for the company came in the end of the 1980s - there were 8.2 million copies of 407 recordings produced in 1987, 4.7 million copies of 185 records in 1988, and 2.1 million copies of 692 records in 1989. But after this the business really languished. By 1991 the company was pressing 1.4 million copies but in 1994 it issued just 100,000. The following March the company closed.